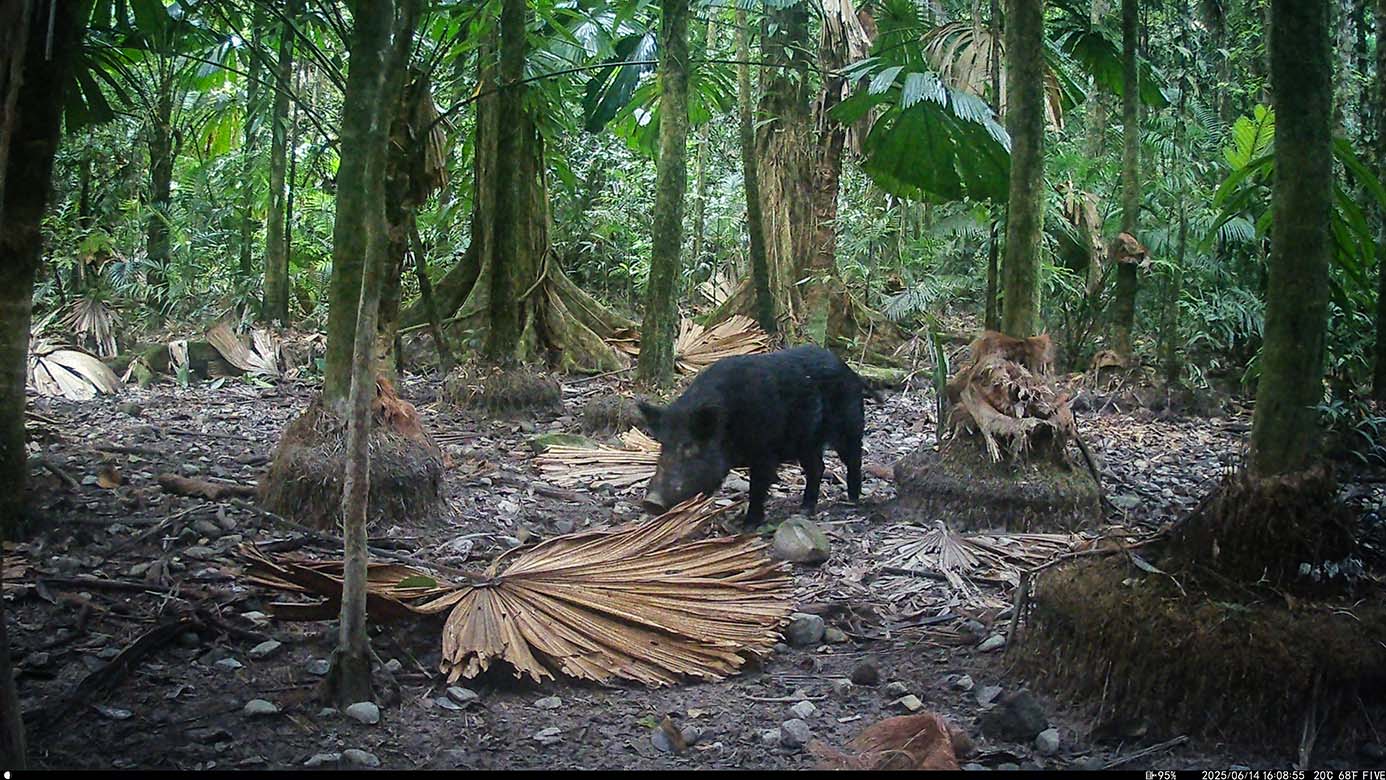

Camera Traps – June 2025 accrued 57-cassowary sightings, 22-dingoes and 105-feral pigs. Against the cumulative monthly average, cassowary numbers fell by 48%, dingo-sightings decreased by 46% and feral-pig numbers also dropped by 48%. Against June 2024, cassowaries were 4% fewer, dingo numbers fell by 51% and feral-pig numbers decreased by 46%.

Image highlights from Camera Traps – June 2025

Keeping up with the cassowaries

Introducing Wobbly … the latest offspring of Crinklecut

Delilah & Scaramanga

Daintree World Heritage Dingoes

Feral-pig fecundity

Backward step for freehold conservation

Byron Bay-based Rainforest Rescue claims to purchase and protect land containing intact high-conservation value rainforest in the Daintree, but have recently decried the unexpected operational costs and red-tape relating to their planned natural habitat restoration of former agricultural land in the far North Queensland region.

Most landholders within the Daintree Rainforest know all too well the expenses and obligations that come with freehold land ownership. They also understand that to provide services and infrastructure to their communities, Local Government raises rates revenue from statutory land valuations upon freehold properties and also from charges levied upon development applications.

When conservation constraints are invoked across freehold properties, in ways typically associated with publicly-owned reserves, landholder obligations become more economically challenging, particularly since public lands do not pay any rates to Local Government whatsoever, but are also fully-subsidised to provide tourism with the illusion of free and unrestricted access. Putting this disparity into perspective, freehold land in Queensland is valued 75.6-times higher than public land gazetted for conservation.

As ‘conservation’ is the majority land-use within the Douglas Shire and tourism is the dominant industry, World Heritage-listing, Endangered Ecological Community-listing and National Heritage-listing, for both natural and Indigenous cultural heritage values, under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, constrains development and should rightfully diminish valuation in conformity with State conservation depreciation, but when ‘tourism’ is attributed as the ‘highest and best use’ for valuation purposes, land valuation greatly increases from former farming concessions.

It appears that Rainforest Rescue now finds itself disadvantaged, as all freehold landowners within the Daintree, but challenging Local Governments’ statutory revenue raising entitlements, is probably less likely to succeed than lobbying State Parliamentarians to add ‘conservation’ to ‘exclusive use as a single dwelling house or for farming’ allowances and concessions under Subdivision 2, Division 5 of the Land Valuation Act 2010.

For many years, Douglas Shire Council maintained pro-active support of freehold landholders through a Rates Incentive for Conservation Policy, with up to 50% rate-relief for inscribing a conservation covenant upon the property title. This video of the Special Meeting reveals Council rescinding the policy on 24th June 2025.

An unsuccessful attempt to defend the policy’s retention stressed the importance of maintaining the Shire’s environmentally significant status, eco-credentials and tourism-ranking in high-standing. However, World Heritage-listing of rainforest and reef ensures that the Shire will never be regarded as having insignificant environmental status, whilst the Shire’s eco-credentials were already gangrenous with green-washing long before Council rescinded its one and only conservation policy that actually improved both the environment and also the well-being of resident landholders.

On a point of clarification, eco-tourism is defined as ethical travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people and communities. Council extracts tourism revenue from visitors into the Daintree Rainforest through ferry fees and in 1999, when Council funded CSIRO to develop the Tourism Simulator Project and investigate visitor-willingness to contribute to conservation costs as a function of ferry-fee increases, 15% of travellers had already shown their unwillingness to pay $7 for a one-way-crossing. Upon evaluation of survey-data and through analytical extrapolation, CSIRO projected that increasing ferry-fees to $10 per-crossing would deter another 15% from paying, clearly verifying the inverse-relationship between increased ferry-fees and visitor willingness to pay for both the ferry-service and also support ecotourism in the rainforest area north of the Daintree River. Only 43% of survey-respondents indicated their willingness to pay $50 per two-way crossing, but now that the cost has risen to $51, it is unknown how many travellers actually turn away, but from the perspective of an ecotourism business operator north of the Daintree River, Council’s 364% increase in single-vehicle ferry-fees, since the Daintree Futures Study (DFS) recommended a 143% increase, manifestly lessens competition. Also, ferry queuing, which has been known to extend to two-hours in both directions, detracts from visitor willingness, as does the inequality of having to yield position in the ferry queue to allow other people in buses and cars inequitable priority access onto the ferry.

The DFS clearly identified that the Daintree ferry was a major source of revenue to the Council, through fees and charges far exceeding the operating costs paid to the contractor and that this revenue was incorporated into the Shire’s operational fund. Council has progressively increased ferry-fees to $51 per two-way crossing to access this world-class attraction and contrary to CSIRO modelling projections, if the number of willing travellers does not diminish because of increased ferry-fees, as Council asserts, revenue from ticket sales should increase from $3.5-million (that ticket commissioning was estimated upon prior to the 1 July 2021 ferry-fee increase) to $5.26-million per-annum, commandeering the bulk of the consumer surplus from which north-of-the-Daintree-River’s conservation economy is otherwise dependent.

Daintree Rainforest Foundation Ltd has been registered by the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission and successfully entered onto the Register of Environmental Organisations. Donations made to the Daintree Rainforest Fund support the Daintree Rainforest community custodianship and are eligible for a tax deduction under the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997.